Dr. Ken Williams has transplanted over 10,000 hair follicles into his own scalp.

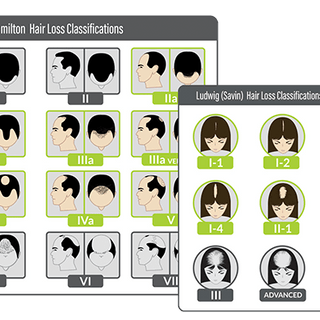

Not in one sitting—that would be madness. Over five separate surgeries spanning years, the Irvine-based hair restoration surgeon methodically addressed his own Norwood 5-6 pattern baldness using follicular unit excision, the technique he literally wrote the textbook about. Two textbooks, actually. Hair Transplant 360, editions one and two, co-authored with Dr. Sam Lam, are considered the definitive surgical guides to FUE—the Bible of modern hair transplantation.

So when Williams talks about what works and what doesn't in hair restoration, he's not speaking theoretically. He's speaking from experience measured in thousands of grafts and decades of living with progressive hair loss.

"I'm a personal user of this model," Williams says, holding up an Xtrallux device, "and I do believe that it's helping me to maintain the density of my hair."

That statement carries weight. This isn't a hair restoration surgeon recommending something to patients while quietly ignoring it himself. This is someone who understands hair biology at the cellular level, who has access to every treatment option available, who has already invested significantly in surgical restoration—and who still considers laser therapy essential enough to use it himself.

Beyond the Knife

Williams practices what he calls "medical and surgical management" for hair loss. The distinction matters. Surgery moves hair from one place to another. Medical management tries to keep hair where it already is.

"It's very important to understand that after surgery is complete," Williams explains, "medical management maintains the current natural density or the existing natural density of the patient."

Think of it this way: if you transplant 10,000 grafts but lose another 5,000 non-transplanted hairs over the next decade, you're running backwards. The transplanted follicles—relocated from the permanent zone at the back of your head—should last a lifetime. But the native hairs around them remain vulnerable to the same genetic programming that caused hair loss in the first place.

This is where medical management enters. DHT inhibitors like finasteride. Minoxidil for stimulation. Platelet-rich plasma injections. And what Williams calls "regenerative therapy"—low-level light therapy delivered through laser caps.

"Laser light therapy, along with medical management, plays an important role in keeping that density for all of a person's life," he says.

The Evolution of Photons

Williams has witnessed the evolution of laser therapy technology over the past fifteen years. Early devices delivered what he calls "a low amount of fluence and energy"—not enough photons reaching the scalp to make meaningful biological changes. The caps were bulky, the diode counts low, and the results inconsistent.

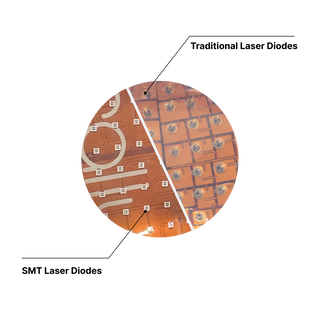

"The evolution of low laser level light therapy in the past 15 years has been remarkable," Williams notes, "starting from a low amount of fluence and energy in these laser caps to now where we have a tremendous amount of laser diodes."

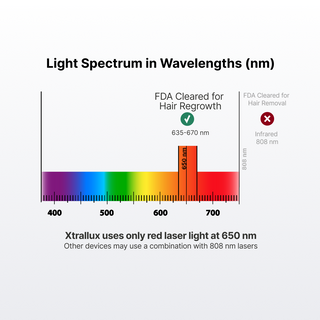

What changed isn't the underlying biology. Light at specific wavelengths has always been capable of influencing cellular behavior. What changed is engineering: more diodes, better coverage, optimized wavelengths, improved power delivery. The photons themselves haven't gotten smarter. We've just gotten better at deploying them.

Who Needs LLLT Most

Williams emphasizes starting early. "Hair loss begins at a very early age, especially if there's a genetic component to it."

For younger patients showing early thinning, he recommends laser therapy before significant loss occurs. Prevention is easier than restoration. You can't bring back a follicle that's been dormant for a decade, but you might extend the productive lifespan of one that's still functioning.

And after surgical restoration—after those thousands of transplanted grafts have been meticulously placed—medical management becomes even more critical.

"Laser light therapy is an important part of the therapy for patients who want to maintain their hair after hair transplant surgery, and especially for those patients who are at greater risk because of androgenetic alopecia or the fact that their parents or brother or aunt or uncle may have alopecia."

Genetics loads the gun. Medical management tries to prevent the trigger from being pulled.

The Personal Equation

Perhaps the most telling detail in Williams' endorsement is the simplest: "I'm a personal user of this model."

He's had five hair transplant surgeries. He has access to every pharmacological intervention available. He's conducting research on stem cell therapies. He's literally trained other surgeons on advanced restoration techniques.

And he still uses laser therapy himself.

That's not an endorsement in the traditional marketing sense. It's a data point. When someone who literally wrote the Bible on hair transplantation chooses to use laser therapy on his own scalp, it suggests the biology is real, the benefits are tangible, and the approach is worth integrating into a comprehensive strategy.

"As you know, as we get older, even despite beyond medical management, there could be a potential to lose hair," Williams says. The resignation in that statement is notable. Even with everything at his disposal, hair loss remains a biological force to be managed rather than conquered.

But management matters. And in Williams' professional and personal experience, laser therapy—specifically, high-quality devices with significant diode counts and reliable manufacturing—plays a meaningful role in that management.

He wrote the book on surgical hair restoration. What he uses on his own head tells you what he really believes about maintaining density over time.